A nearly great book reduced to a merely good one by a literal-minded editor

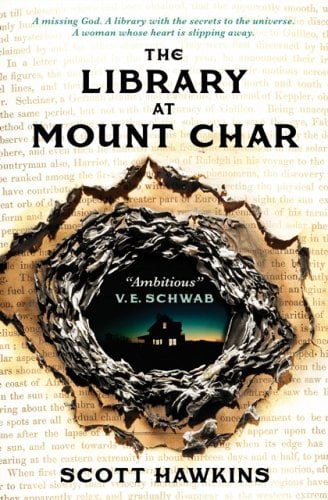

I really liked this book, is the first thing to say. It’s original and genuinely horrifying. The premise is, roughly, that an immortal demigod known only as ‘Father’ took a group of American children and trained them to be his successors as rulers of the Universe. Their training took place in the Library of the title, an interdimensional rift containing the sum total of inhuman knowledge. Each of the children was firmly restricted to studying only one area – languages, or medicine, or combat. As you will already have worked out, much of the drama derives from the fact that the children, of course, didn’t stay in their own lanes. The drama progresses with the various children – now adults – battling to succeed Father, while caught in the crossfire are numerous humans from our world, gradually increasing to include virtually everyone.

So, what goes wrong with the book? Not enough to knock it down from a great read. The problem is with the final third or quarter of the book. The plot is basically over. But now we get what amounts to a massive, lengthy info dump, the kind of thing that would’ve been in the manual of a ’90s videogame. The big problem with this info dump, for me, is that it was all exactly what I was expecting.

I don’t know exactly what happened but I will happily bet you any money I make this week that Hawkins wrote the book without that final section. Along came an editor who demanded that the backstory be filled out, lest the reader be permitted to use their imagination. And so, we have a fantastic work of imagination that declines to let you use your own.

A better editor might have allowed this exposition to be more evenly distributed throughout the book, so that we don’t get so much at the end. There’s clearly some attempt to do just this, but it’s not been done enough to fix the overlong final section.

There’s always a balance to be struck between telling the reader things and letting them work it out for themselves, granted. But the weight should always be with the latter. Reading is a work of imagination. Filling in the gaps left by the author – and there are always gaps – is the essence of the activity. The world’s zealous editors would do well to remember that.

I may receive a commission from the links above.

If you’d like me to keep mouthing off about books what I like, help me out by donating: