Online poetry culture is fascinating. The web has dramatically changed how we interact with language, so it’s no surprise that it’s affected poetry and our appreciation of it, too. Look at the way that ‘This is Just to Say’ has somehow become a meme, something as malleable as a screenshot from The Simpsons. Or the way that various people on Instagram have successfully wound up an entire generation of poets by writing the kind of thing you might find on a fridge magnet in a gift shop and publishing it as poetry.

I don’t like any of those Instagram poets, because they all write very badly, but I don’t think that what they do is not ‘real poetry’. It’s just bad writing. To illustrate my point, here is a typical poem by Instapoet Robert M. Drake:

The best kind

of humans are

the ones who

stay.

I’m not going to pretend this is good writing because it isn’t and I’m an honest person by both conviction and habit. It’s very bad, but it does illustrate some features that I think are distinctive in web poetry: short line length, no rhythm (i.e., it’s ‘free’ verse) and the use of line breaks for emphasis, almost instead of rhythm. It’s also irritatingly typical in its failure to even observe grammatical agreement. This happens a lot in English anyway (‘a number of rooms are free’ is the famous example; since ‘number’, the subject, is singular should the verb also be singular ‘is’ rather than plural ‘are’? Or should we say ‘are’ because what we’re ‘really’ talking about is (are?) the rooms?). But if you’re going to do this kind of thing in a poem, you should really interrogate it, rather than just leave it there. Indeed, just having ‘kinds’ would be better poetically and grammatically, as presumably there’s more than one kind of human who stays, anyway.

It’s shabby writing from top to bottom and asks endless questions which it makes no attempt to answer. Should I stay even after someone’s told me to leave, so that I can be the one kind of human who are the best? Why does it say ‘humans’, as though the speaker in the poem is a non-human? Or is there an an assumption that non-human animals do stay? Or that they don’t?

A lot of people find it irritating that someone like Drake, who, as we have seen, can barely write at all, is out there getting published as a poet, but there’s no discernible solution to this kind of ‘problem’. You don’t have to read him and my advice to you is that you don’t.

So, people who mainly get their poetry via Instagram have, by popular consensus, made Robert M. Drake a poet. This is fine, as far as it goes. But I didn’t write this blog to be mean about Drake. Because something far odder is what popular consensus has done to the writing of John Donne.

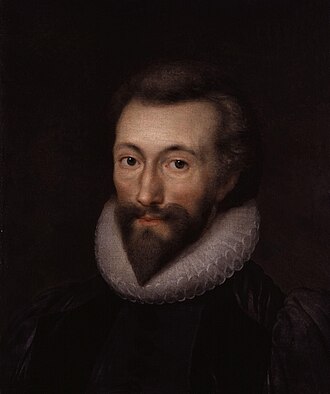

John Donne was a poet, who wrote in both Latin and English. He also wrote a lot of prose, some of it sermons which he wrote and delivered in his day job as the Dean of St. Paul’s. He’s still well-known as a poet, but the lines he’s most famous for are these, from a devotional work he wrote shortly after recovering from a near-fatal illness:

No man is an island, entire of itself; every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main; if a clod be washed away by the sea, Europe is the less, as well as if a promontory were, as well as if a manor of thy friends or of thine own were; any man’s death diminishes me, because I am involved in mankind; and therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee.

(I’ve modernised Donne’s spelling and punctuation.)

You’re probably familiar with this passage or at least with some of the famous lines: ‘No man is an island’ and ‘for whom the bell tolls’ have each been quoted over and over again and used as the titles of various songs, books and films. It’s become one of the best-known statements of humanism and will probably remain well-known for as long as humanism is the default philosophy of our culture.

But the strange thing about this passage is that, in the last week alone, I have seen two different people, in different contexts, describe it as one of their favourite poems. But it’s not a poem. Donne wrote it as prose. He didn’t set it out as verse and it reads like prose. And yet, a lot of people, not just those two, think it’s a poem. Even better, one of them actually laid it out as verse, chopped up mostly at the semicolons but sometimes at the commas, like this:

No man is an island, entire of itself;

every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main;

if a clod be washed away by the sea, Europe is the less,

as well as if a promontory were,

And so forth.

Now, I didn’t want to say that Drake’s poem is not a poem. I am a little more confident in my view that this excerpt from a devotional tract is not a poem. I at least have authorial agreement on that point. Nor does chopping it up at the breaths make it into a poem. If Donne had wanted to express these ideas in iambic pentameter, he certainly could have done, but there’s no iambic pentameter here.

So, why do people think this is a poem?

Firstly, John Donne was a famous poet. It’s natural to come across some famous lines by a famous poet and assume they’re poetry. Or, it’s natural if you can’t hear poetic rhythm, which I am 100% certain most people cannot. A case in point can be seen in the ‘versified’ version above. You don’t need to beat out the rhythm on your desk or count on your fingers to see that these ‘lines’ don’t make any poetic sense.

Secondly, bits of it almost sound like a poem. ‘No man is an island’ starts us off with a series of trochees, which sound enough like iambs to mislead the casual reader. The other famous bit is even closer to iambic pentameter: ‘and therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee‘. If you put a line break before ‘and’ and after ‘whom’, it’s a perfect iambic pentameter, which is quite pleasant. Even better, the same line is commonly misquoted, but in a way that emphasises the iambic because it relies on monosyllables: ‘send not to know for whom the bell tolls’.

That said, a few iambs does not make a poem. Iambs crop up all over the place in English and a lot of good writers, especially speechwriters, use them on purpose for this reason. Winston Churchill’s war speeches are a good example: ‘if the British Empire and its Commonwealth last for a thousand years, men will still say, “This was their finest hour“.’1 Churchill was deliberately channelling the St. Crispin’s Day Speech, with the emphasis on people looking back on the battle after it’s all over, so the iambs are appropriate here both to make it memorable and to place it in a lineage of great British oratory about great victories against the odds.

Nevertheless, while people endlessly quote this and Churchill’s other war speeches, often while discussing football, I’ve yet to see anyone mistake any of them for a poem.

There’s another way in which the ‘No man is an island’ passage seems like a poem, and it’s one which relates to Drake’s poem: the didactic tone. Donne was being didactic because he was essentially giving a sermon. They’re meant to be didactic. Some poets (and their online audiences) have absorbed the idea of deriving lessons from poetry. Even if they’ve never read In Defence of Poetry, they’re looking to poets as the ‘legislators of the world’. Look at both Drake and Donne: ‘The best kind / of humans are’ [etc.], ‘No man is an island’. These are both stated simply as facts. There’s no suggestion that disagreement might be a possibility. The poet has spoken. By contrast, in ‘Their finest hour’ there’s plenty of grand claims, but the overall intent is persuasive. It’s rhetoric, rather than a lesson. This, I think, is one of the reasons people don’t mistake it for a poem. The tone is wrong for what they associate with poetry, or at least with random lines of poetry printed over a stock photo of a sunset.

Am I doing this right?

Donne goes on to extend and complicate his metaphor, because he was a good writer. Extended metaphor is a technique we associate with poetry and especially with the metaphysical poets, of whom Donne is the exemplar in English literature, so this is another reason people read this and think it’s a poetry. Drake, of course, is incapable of extending a metaphor. His whole ten-word poem is this one clunky claim about a kind of humans(?), whereas Donne’s point is made in just the five oft-quoted words, but he then goes on to explain and enliven what he’s said, and does the job so well that he ends by introducing another entry in your Big Book of Clever Quotes of choice, but it’s a similarly lecturing tone. He doesn’t say, ‘It could be said that the bell tolls for thee’.

Many of the odd bits of poetry that get quoted like this are similar. Think of Shakespeare’s Sonnet 116 and its (wholly inaccurate) claim that ‘Love is not love / Which alters when it alteration finds, / Or bends with the remover to remove’. Or of that dreadful, dreary passage from Corinthians people love to read at weddings (‘Love is patient, love is kind, it does not make the assembled wedding guests stab themselves in a hand with a fork, just to feel something, anything, other than this.’2). (Obviously, I know this isn’t a poem, either, but I bet you the people who read it at weddings don’t.) The point is, the tone is the same: sweeping, grandiose statements, divested of irony, stripped of context, mistranslated, essentially bowdlerised into something that is intended to feel in some way inarguably true, even when, it palpably isn’t and possibly wasn’t intended to be.

It’s probably understandable that some people prefer Drake’s didactic poem over, to pick an example at random, a poem that asks you to put yourself in the place of someone driven to a murderous rage by the fish that he unwisely turned into an anthropomorphic abomination, especially when they’re just scrolling past. Ultimately, it doesn’t matter if people enjoy Drake’s poetry or think that Devotions upon Emergent Occasions is a poem. But there ought to be more to poetry than a lecture.

- Note that the ‘poetic’ stress falls in a different place than the sense would suggest. No one wants to say ‘This was their finest hour’. We always say ‘This was their finest hour’ – as did Churchill. ↩︎

- In the King James Bible, this passage is about ‘charity’, rather than ‘love’, giving us yet another reason to reject the New International Version. In the original Greek, it’s about ‘agape’ (ἀγάπη), prononuced with three syllables ‘a-GAH-pay’, ‘AH-guh-pay’ or ‘AG-a-pay’ (ɑːˈɡɑːpeɪ, ˈɑːɡəˌpeɪ, ˈæɡə-). It really means God’s love for humanity, which at least if you believe in it makes far more sense than looking at human love and saying it doesn’t envy, of all things. In any case, it obviously has no application to your wedding. ↩︎